By Jennifer Throndsen

Being an intermediate grades educator in today’s classrooms has become increasing challenging. From trying to capture the fleeting attention of an adolescent to addressing the widening gaps in learner variability, meeting the needs of all learners can feel exhausting.

Being an intermediate grades educator in today’s classrooms has become increasing challenging. From trying to capture the fleeting attention of an adolescent to addressing the widening gaps in learner variability, meeting the needs of all learners can feel exhausting.

Finding ways to scaffold in classrooms with a mix of students – some who read like second graders and others who read like they’re ready for college – can be overwhelming. Luckily, there are low-prep, easy to implement, research-based strategies teachers can employ to address these challenges.

As a veteran educator with 20+ years of experience serving as an educational consultant for schools, districts, and state departments of education, I spend most of my days in schools supporting educator growth and development to improve impact on student learning outcomes.

Every day I encounter the diversity of capabilities of students and the great opportunity we have as educators to address those needs. Knowing that all students deserve to engage in grade level content, with the appropriate scaffolding to do so, I’ve supported countless educators in making small changes to their practice that lead to meaningful impact. Here, I’ll share three strategies I’ve found highly effective.

1 – Frontloading Key Concepts or Vocabulary

When I served as the Multilingual Coordinator for a school district in Alaska, we experienced a 50% gain in the percentage of students obtaining proficiency or making progress towards proficiency in just two years, going from 25 to 75%.

One of the most influential changes we made was consistently employing frontloading of the key concepts or vocabulary that our students would need to engage in Tier 1, or core instruction.

Specifically, we provided our MLLs with the key knowledge and skills they would need to have greater access to the classroom instruction in advance of the instruction. For example, if students were going to read about the movement of matter among plants, animals, decomposers, and the environment (NGSS 5-LS2-1), the teacher would introduce the key vocabulary needed to understand the essential concepts with a small group of students prior to the whole group instruction.

This might include using a short video that outlines the concepts, providing a model with examples and pictures of how this process works, or engaging students in an explicit vocabulary routine for the key terms, basically anything that builds their knowledge.

In this scenario we used the strategy with our MLLs, but this strategy can be useful for any students who may require additional background knowledge and language to increase their access to the core content.

In fact, I was in a school last month with teachers who I had trained on frontloading, and they expressed how they had seen the benefits not only in students being better able to engage in the instruction, but also in their attitudes and levels of enthusiasm. Students felt like they had something to contribute to the class discussion given their enhanced knowledge.

Whether you can pull a small group of students prior to essential content learning or you can partner with an English language development teacher to have them provide the learning prior to the lesson, consider the impact frontloading could have on increasing student engagement as well as learning.

2 – Making Connections to Prior Experiences

When we create opportunities for students to make connections as they work to actively construct meaning, the result is increased comprehension of the topic at hand (Hacker & Tenent, 2002; Kucan & Beck, 1997; Miller, 1985; National Reading Panel, 2000).

To elicit such connections, we want to offer learning opportunities that encourage students to pull from personal experiences that they can bring to bear on the text – or the background knowledge they’ve learned from other texts or learning experiences on the topic.

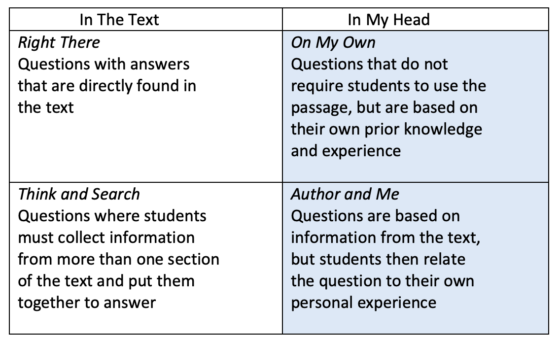

By encouraging students to make connections from their prior experiences, you can enhance the students’ ability to make meaning and increase the likelihood the new learning will be retained (Short, 1993). One well researched and evidence validated strategy that fosters the intentional making of connections is Question-Answer Relationships, or QAR (Raphael, 1986).

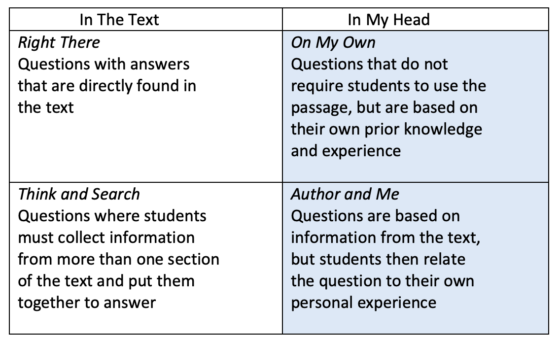

QAR uses four types of questions that are divided into two categories: (1) in the text and (2) in my head. The four question types are represented in the table below. Specifically, it’s the On My Own and Author and Me questions that offer explicit opportunities for students to make connections.

QAR Question Types

So, if you are engaged in learning about a topic and you can foster specific opportunities for students to consider their prior knowledge and experience and how it connects to the new learning, this can be a powerful strategy for scaffolding students in the new content and lead to increased success in learning.

So, if you are engaged in learning about a topic and you can foster specific opportunities for students to consider their prior knowledge and experience and how it connects to the new learning, this can be a powerful strategy for scaffolding students in the new content and lead to increased success in learning.

3 – Partially Completed Graphic Organizers

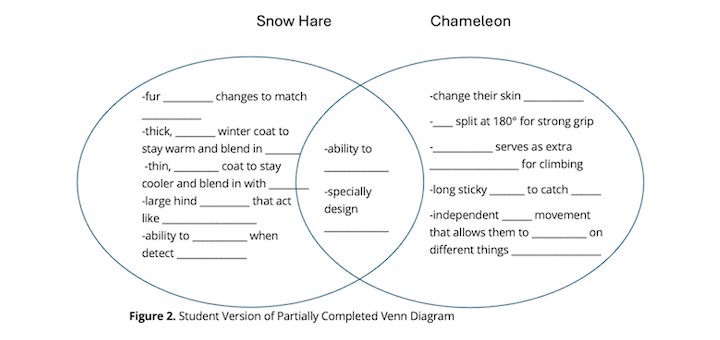

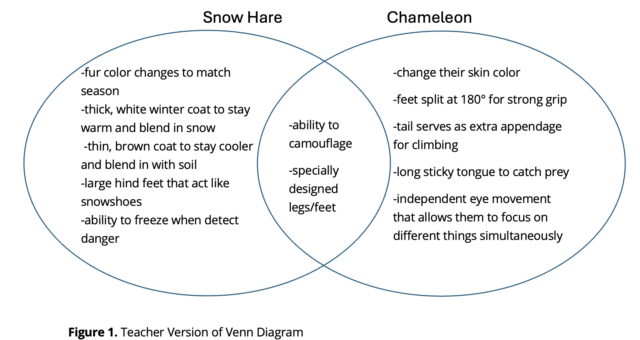

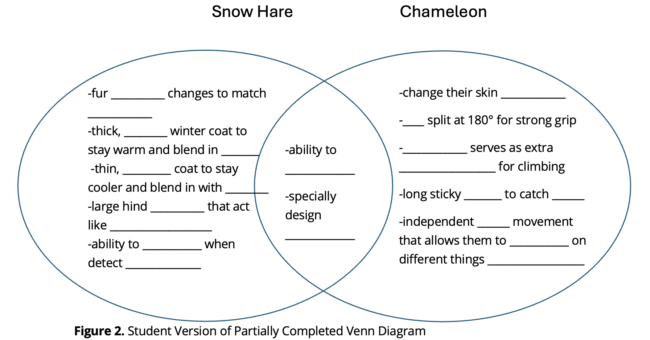

A partially completed graphic organizer can be a Venn diagram, timeline, concept map, or really any other graphic organizer that the teacher partially fills in to help students hone their focus, more easily notice relationships, and increase retention of the new material – all while also reducing the cognitive burden for developing readers and writers.

To implement this strategy, here are four steps you can use:

Step 1: Choose the graphic organizer that best aligns with the intended learning outcome (e.g., a timeline for charting a series of events).

Step 2: Complete a draft of the graphic organizer that contains all the key details.

Step 3: Identify what information from the draft is the most important and replace that information with blanks.

Step 4: Explicitly guide students in completing the partially-completed graphic organizer as they engage in the reading or learning task.

Let’s use an example. Let’s say you are going to ask students to compare how two animals, the snow hare and the chameleon, adapt to their environment to survive. In this case, you would likely choose a Venn diagram as the graphic organizer.

You will then go through and write out the key information you would want students to capture during the lesson on the graphic organizer. Then, you will go back through and identify the most important details and replace those details with blanks.

Then, as you teach the lesson, you will help direct students’ attention to the critical information and fill in the missing elements. When the lesson is completed, they will have all the details on the organizer but will have filled in the most critical details with less stress on working memory, therefore leading to increased retention and learning (Ellis, 2004; Mede, 2010).

Final Tips on Scaffolding Learning For All

First, your beliefs about what a student is capable of accomplishing is one of the most impactful factors on their performance (Hattie, 2023). If you truly believe a child is capable of learning at high levels, then they will do so.

I not only say this from experience, as I have taken a class of fourth graders who entered at 40% proficient in reading to 96% (in a Title I school in failure status), but also through the numerous teachers I have supported as they accelerating learners who had yet to experience strong success in school.

Additionally, remember scaffolding is meant to be a temporary support. As students demonstrate the ability to handle more responsibility, it is essential that we remove more and more of the support so that in time they can do it independently.

Going back to the partially completed graphic organizers, partial completion is a strategy that with practice and time can be completely left to the students’ responsibility as they demonstrate more competence. We can slowly require more of the graphic organizer to be completed with less support and teacher direction. Be sure to be mindful of your students’ progress and slowly peel that extra level of support away as they grow.

Finally, when we scaffold effectively, we are not lowering the expectation for some students. We are maintaining the grade level expectations while creating learning conditions that afford students the opportunity to accomplish the grade level task with support.

Over time we gradually adjust our support as students acquire more skills. Unlike differentiation, where we often alter the task and lower the cognitive demand or expectations, we can use scaffolding to maintain high expectations while leveraging the necessary supports a student may need to achieve grade level success.

Dr. Jennifer Throndsen is the author of Raising Up Readers: 25 Scaffolding Strategies to Help Students Access Challenging Text (Solution Tree, 2025) which includes additional ideas of how to scaffold learning. She is a former elementary and middle school teacher, instructional coach, district office specialist, and state director, known for her impact on student learning and passion for student-centered learning. Visit her website for additional resources and more information.

Dr. Jennifer Throndsen is the author of Raising Up Readers: 25 Scaffolding Strategies to Help Students Access Challenging Text (Solution Tree, 2025) which includes additional ideas of how to scaffold learning. She is a former elementary and middle school teacher, instructional coach, district office specialist, and state director, known for her impact on student learning and passion for student-centered learning. Visit her website for additional resources and more information.